This post is a reflection on my learnings from the course CS 185/285: Deep Reinforcement Learning by Sergey Levine, particularly the lectures on imitation learning.

Behavioral Cloning Recap

The concept of behavioral cloning can be traced back to ALVINN. In this setting, the dataset is collected from human driver as follows:

- refers to horizon (the number of time step in one recording).

- is the total number of recordings (episodes).

- We collect observations() and actions() sequentially.

The training objective of the neural network is:

We aim to train a policy that maximizes the likelihood of taking action given observation .

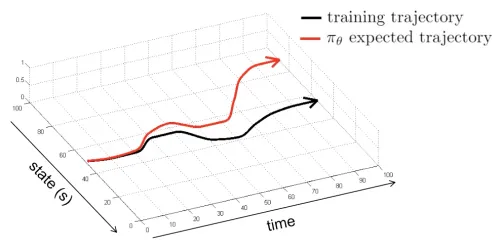

©️Sergey Levine

The training trajectory represents the ground truth demonstrated by human experts. As you can see, the difference between the policy and the ground truth grows increasingly large over time. This makes naive behavioral cloning not work.

Why It Doesn’t Work

Let me interpret why it fails using my own language.

(1) Performance ceiling: Supervised learning optimizes a loss function to prevent both overfitting or underfitting. Consequently, the model tries to average out the expert’s behavior. Therefore, we will NEVER PERFORM BETTER THAN THE EXPERT. This explains the minor gap visible even at the start of the trajectory.

(2) IID Violation. Behavioral cloning violates the iid assumption, which is the CORE of supervised learning. Why? Because the current action affects the next observation . This causes errors to ACCUMULATE.

- The expert’s action leads to an expert observation .

- However, our trained policy produces an approximation , which leads to a slightly different, non-expert observation .

(3) Unfamiliar States: We eventually get lost in a state we are unfamiliar with! The expected next action was trained on the expert’s , NOT on the drifted . Because the trained policy has never seen this drifted state, it doesn’t know where to go. The next action becomes even more unpredictable, leading to even greater error.

Remark

A formal explanation for this is distribution shift, which I think it is specifically related to covariate shift.

- We train our policy on

- We test our policy on

- The problem is that

This is like having a training set with realistic cats and dogs:

But the test set has cartoon-style cat and dog:

No Ergodicity

Sergey gave a great analogy about “falling into an unknown state”, comparing it to high wire art.

1974 Hess’s ad, with an image of Petit’s walk across the Twin Towers

If the artist falls off, he can never get back to the rope. This is exactly what Nassim describes in his book Skin in the Game: Hidden Asymmetries in Daily Life as a lack of ergodicity. Naive behavioral cloning lacks ergodicity. When the policy drifts into an unfamiliar state, it cannot recover. It is like an absorbing state in mud.

The Quick Fix

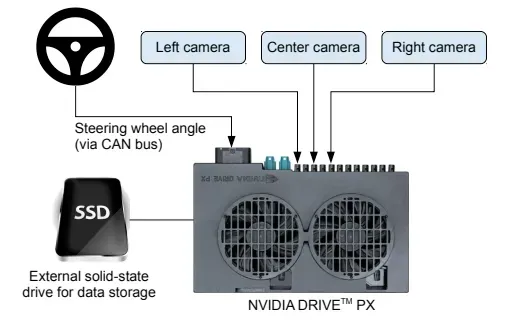

The paper 📄End to End Learning for Self-Driving Cars proposes a clever trick to “rescue” the agent back to the expected track. In Taleb’s view, this adds ergodicity to the system.

The idea is to mount two extra cameras capture the “unfamiliar state” (being off-center) and label them with a “rescue” action.

©️End to End Learning for Self-Driving Cars

For example,

- the observation from the left camera is labeled with a “turn right” action.

- the observation from the right camera is labeled with a “turn left” action.

By mixing this data into the training set, the policy now has better actions for states that were previously “unfamiliar”. It learns how to escape the absorbing mud, creating an ergodic system.

The Better Fix

If you are interested in more robust solutions, take a look at these: